Como pueblos indígenas, hemos vivido en armonía con la naturaleza en uno de los últimos bosques tropicales no perturbados de Panamá. Durante siglos, hemos dependido de los ríos para el transporte sostenible y consideramos el bosque como nuestra farmacia natural, que nos proporciona acceso a plantas medicinales en cualquier momento. Uno de nuestros principales objetivos es fortalecer nuestras tradiciones culturales relacionadas con la protección del medio ambiente, la conservación del agua, la agricultura y la coexistencia con la tierra.

Biodiversidad en Panamá

A pesar de cubrir un área ligeramente más pequeña que el estado de Carolina del Sur en EE. UU., el istmo en forma de S de Panamá es una de las regiones más vibrantes y biodiversas del planeta. Como un puente terrestre entre América del Norte y América del Sur, ha servido como un corredor biológico vital desde el Gran Intercambio Biótico Americano, un evento que inició la migración norte-sur y la mezcla genética de innumerables especies de plantas y animales hace aproximadamente 2.7 millones de años. Además, la aparición del istmo dividió los océanos Atlántico y Pacífico, llevando a numerosas especies marinas por caminos evolutivos divergentes.

Ubicado en latitudes tropicales entre Costa Rica y Colombia, Panamá es un país cálido y húmedo, caracterizado por una larga temporada de lluvias (de mayo a diciembre) y una temporada seca relativamente corta (de enero a mayo). Una cordillera montañosa escarpada divide el interior en dos cuencas hidrográficas distintas: la del Pacífico y la del Caribe, siendo esta última significativamente más húmeda y menos predecible en su clima. La variada geografía física y las intensas condiciones climáticas han fomentado una rica diversidad de ecosistemas exuberantes en Panamá, que incluyen selvas tropicales de tierras bajas, humedales vibrantes, manglares costeros, bosques secos y bosques nubosos de alta montaña. Casi 500 ríos cruzan el país, mientras que aproximadamente 1,600 islas e islotes, muchos de ellos adornados con coloridos arrecifes de coral, salpican sus costas de arena blanca.

Gracias a su notable variedad de nichos ecológicos, Panamá alberga una excepcional diversidad biológica. Aproximadamente 11,000 especies de plantas, incluyendo 1,200 orquídeas y 1,500 especies de árboles, casi 1,000 especies de aves, más de 200 especies de anfibios y más de 200 especies de mamíferos prosperan en Panamá, muchas de las cuales son endémicas, raras y amenazadas a nivel global. Su fauna carismática incluye jaguares, perezosos, tapires de Baird, monos, águilas arpías, quetzales resplandecientes, ranas dardo venenosas de colores neón y cinco especies de tortugas marinas, por nombrar solo algunas. Como un centro para la vida de aves migratorias, Panamá atrae a miles de halcones, águilas y otras aves de presa durante una impresionante migración anual de rapaces.

Conservación y Sostenibilidad

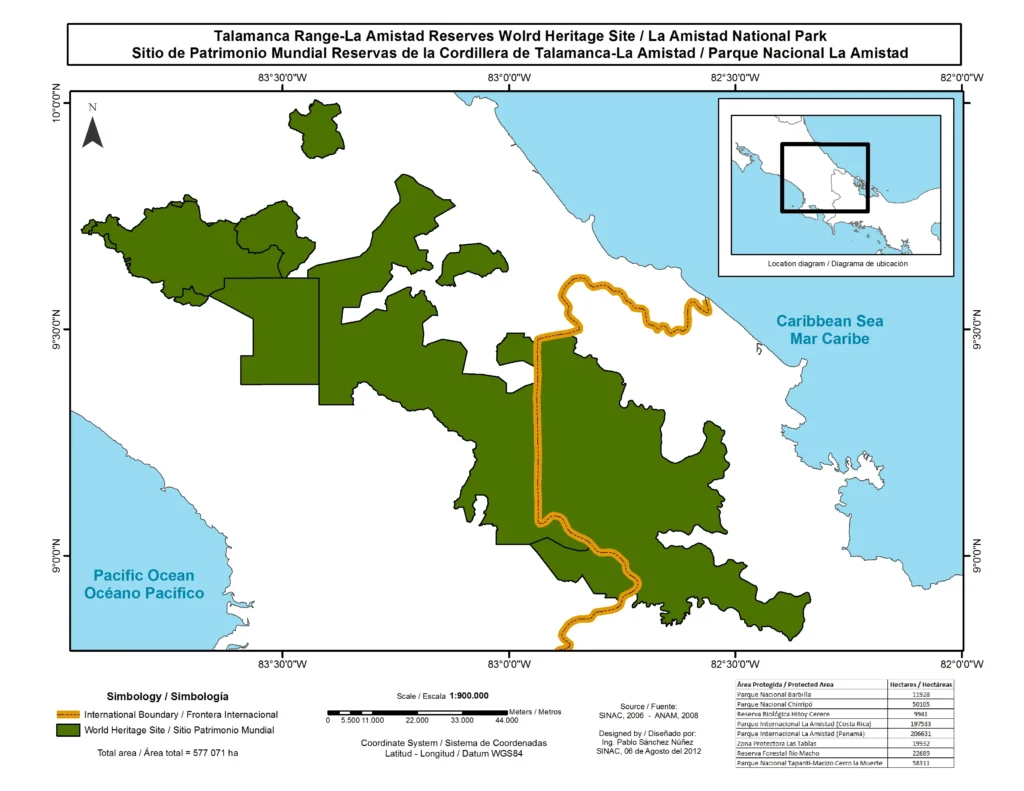

Aunque Panamá ha perdido más de la mitad de su cobertura arbórea desde la década de 1940, la conservación y la sostenibilidad son ahora reconocidas como componentes esenciales de la agenda nacional. Hasta la fecha, el gobierno panameño ha designado aproximadamente 3.5 millones de hectáreas—casi el 40% de su territorio—como áreas legalmente protegidas, incluyendo 13 parques nacionales y zonas marinas. Tres de estas reservas tienen una importancia global y han sido designadas como Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO, incluyendo el Parque Internacional La Amistad en la provincia de Bocas del Toro, que es administrado conjuntamente por Panamá y Costa Rica.

El Parque Nacional La Amistad se extiende a lo largo de la frontera entre Panamá y Costa Rica. La propiedad transfronteriza cubre grandes extensiones de la cordillera no volcánica más alta y salvaje de Centroamérica y es una de las áreas de conservación más destacadas de esa región. Las Montañas Talamanca contienen uno de los principales bloques restantes de bosque natural en Centroamérica, sin que haya otro complejo de áreas protegidas en Centroamérica que contenga una variación altitudinal comparable […] El hermoso y escarpado paisaje montañoso alberga una extraordinaria diversidad biológica y cultural. Los sitios arqueológicos precerámicos indican que la Cordillera Talamanca tiene una historia de muchos milenios de ocupación humana. Hay varios pueblos indígenas a ambos lados de la frontera dentro y cerca de la propiedad. En términos de diversidad biológica, hay una amplia gama de ecosistemas, una riqueza inusual de especies por unidad de área y un grado extraordinario de endemismo.

— Convención del Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO

Riesgos Ambientales

A pesar de los importantes avances en la protección del medio ambiente, los paisajes naturales de Panamá se enfrentan a numerosas amenazas, en gran parte debido a un modelo de desarrollo que prioriza el crecimiento económico sobre la sostenibilidad medioambiental y a una filosofía que sitúa al «hombre contra la naturaleza». Por ejemplo, los planes de desarrollo de la costa caribeña del país, como La Conquista del Atlántico, pretenden abrir la región a nuevas formas de explotación. Actividades como la minería a cielo abierto, la tala de árboles, la ganadería, el turismo y el desarrollo inmobiliario han contribuido a la degradación de la riqueza natural de Panamá. Los problemas medioambientales actuales incluyen la pérdida de hábitats, la contaminación del agua, la degradación del suelo, el tráfico de especies silvestres y el cambio climático antropogénico. Además, los organismos medioambientales de Panamá carecen de fondos suficientes y, en algunos casos, están comprometidos políticamente.

Custodia Indígena

Los pueblos Ngäbe y Buglé poseen invaluables conocimientos etnobiológicos y ecológicos de los bosques de Panamá, que deben ser reconocidos por nuestras comunidades políticas y científicas. Como actores vulnerables cuya salud y medios de vida dependen directamente de la integridad de nuestros recursos naturales, debemos ser incluidos en todos los debates de alto nivel relacionados con la conservación y el desarrollo, tanto a nivel local como nacional. Por desgracia, a menudo no es así. Un aspecto clave del trabajo de MODETEAB es concienciar a la opinión pública sobre el rico patrimonio natural de Panamá, defenderlo de la destrucción imprudente y promover a nuestros pueblos indígenas como los mejores administradores de esta tierra.